Meyer Decision: First Sale Remains a Savings Avenue for Importers

First sale appraisement currently remains a legally viable duty savings avenue, including for transactions with vendors in NMEs.

On March 1, 2021, Judge Thomas J. Aquilino, Jr. of the US Court of International Trade (CIT) issued a lengthy opinion in Meyer Corp., U.S. v. United States, slip op. 21-26, skeptical of the longstanding use of first sale appraisement in non-market economies (NMEs), causing an uproar in the import community — but is this much ado about nothing?

What Is the First Sale Rule?

Under 19 USC 1401a(b), imported merchandise is presumptively appraised for customs purposes according to its “transaction value,” or the “price actually paid or payable for the merchandise when sold for exportation to the United States,” subject to certain additions. In a multi-tiered transaction—that is, with a manufacturer, one or more middlemen, and an importer—more than one sale takes place. The court decisions in Nissho Iwai America Corp. v. United States, 982 F.2d 505 (Fed. Cir. 1992), and Synergy Sport International, Ltd. v. United States, 17 C.I.T. 18 (1993), authorize first sale appraisement, which is the principle that an importer may value the merchandise based upon the first of the sales (i.e. from the manufacturer to the first middleman), provided that:

- the sale is a bona fide sale,

- the goods are clearly destined for the United States and that,

- the “manufacturer and middleman deal with each other at arm’s length, in the absence of non-market influence that affects the legitimacy of the sale price.”

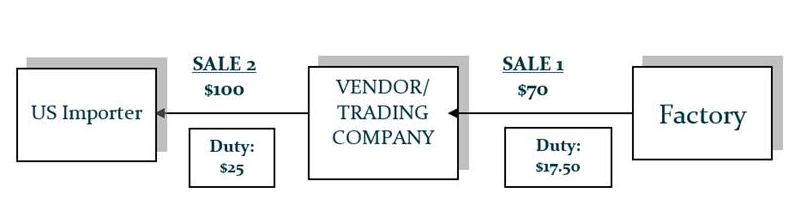

This arrangement can significantly reduce the US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) declared value of merchandise — and thus duty liability, which is most often proportional to value (ad valorem) — by disregarding the profit and other overhead costs that are included in the price that the importer pays the middleman. For instance, consider merchandise subject to a duty rate of 25%, ad valorem, where the first sale price between the factory and middleman/vendor/trading company is $70 and the second sale price between the vendor to a US importer is $100. Under the first sale appraisement, the $30 of profit and overhead costs attributable to the middleman/vendor would not be dutiable, realizing a savings of $7.50, or 30%.

Use of first sale appraisement has become increasingly popular of late amongst importers of Chinese goods, most of which are subject to additional duties under Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974 imposed by the Trump Administration and still effective today.

In addition to court cases, countless CBP rulings across nearly 30 years have vetted first sale appraisement. Generally, when CBP audits an importer’s use of first sale, the importer must produce (1) a detailed description of the roles of each of the parties involved in a multi-tiered transaction and (2) a complete paper trail relating to the imported merchandise that shows the structure of such transaction. Determining Transaction Value in Multi-Tiered Transactions, T.D. 96-87, 30 Cust. Bull. 52 (Jan. 2, 1997). These are the same documents that are required to set up the first sale program and should be retained in the normal course as part of the importer’s recordkeeping obligations. Validating the arm’s length nature of the transaction and pricing can be more complicated in cases where the manufacturer and middleman are related because the circumstances of sale must establish that the relationship did not influence the price paid or payable.

What Did Meyer Hold — and Suggest?

In Meyer, the court reviewed first sale transactions involving related parties and questioned the ability to validate arm’s length pricing for manufacturers based in non-market economies, such as China (PRC) or Vietnam, where the government exercises significant control or influence over prices. The plaintiff, a US importer, imported certain cookware from China and Thailand purchased through middlemen/resellers. In this case, all of the parties in the transaction were related: the Chinese and Thai manufacturers, the third-country middlemen, and the importer were all subsidiaries of the same parent company, Meyer Holdings.

The case began as a first sale audit. CBP auditors determined that the sales from the Chinese and Thai manufacturers to each of their respective resellers (middlemen) were bonafide and the goods in both sales were clearly destined for the United States. Nonetheless, CBP rejected the use of first sale appraisement because Meyer failed to demonstrate that the sales were conducted at arm’s length and that the prices were not influenced by the relationship between the parties. CBP relied in part on the unwillingness of Meyer Holdings to release financial information for the various companies involved in the transaction — because a comparison of the operating margin of the parties is generally part of the arm’s length review. The court sustained CBP’s rejection of first sale appraisement for the same reason, namely a lack of evidence to show the independence of the manufacturers from the middlemen. The court found that the parent company, although not a plaintiff, was not “forthcoming” with the documentation necessary to show an arm’s length transaction, despite having “an interest in seeing these types of matters resolved favorably.” Accordingly, the court determined that the relationship between the parties influenced the price.

The novelty in the Meyer decision is Judge Aquilino’s interpretation of the requirement that the arm’s length transaction be free “of non-market influence,” which creates a presumption that transactions involving a non-market economy are inherently compromised for purposes of first sale appraisement. The third Nissho Iwai factor requires that the “manufacturer and middleman deal with each other at arm’s length, in the absence of non-market influence that affect the legitimacy of the sale price.” However, this requirement has traditionally been viewed, by both CBP and the industry, holistically as a single factor. Notably, the Meyer’s court separated the “absence of non-market influence” into a separate fourth factor, which is nearly impossible to satisfy in the case of non-market economies. The court observed that the “real costs of inputs from the PRC are suspect, given its status as a non-market economy country,” and expressed its “doubts over the extent to which, if any, the ‘first sale’ test of Nissho Iwai was intended to be applied to transactions involving non-market economy participants or inputs.”

This position is unusual, in that neither CBP nor other court decisions have ever suggested or considered that the Nissho Iwai “non-market influence” requirement indicates influence by the government in a non-market economy, rather than a distortion of prices by the companies themselves.

What Should Your Business Do?

First sale appraisement currently remains a legally viable duty savings avenue, including for transactions with vendors in NMEs. Meyer presents an original interpretation of the Nissho Iwai first sale factors at the trial-court level. The court itself noted that “the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit could provide clarification” on the application of first sale to NMEs, which, if the case is appealed, could take years. Moreover, the case was ultimately decided on a separate, fact-specific basis limited to the related parties involved. Therefore, the breadth of the opinion and implications for businesses whose supply chains operate under a first sale model in NMEs is uncertain, but unless and until clarified by the Court of Appeals, likely extremely limited.

Companies that have implemented first sale, including those with vendors in NMEs, should rest assured that the program is legally sound. Companies that purchase goods through a trading company or middleman should continue to consider the implementation of a first sale program because the duty savings can be significant, particularly for importers of Chinese goods subject to the Section 301 tariff.

Nonetheless, this decision may trigger increased CBP scrutiny of the first sale program. Companies with such a program should study the implications of the Meyer case and, at a minimum, audit existing programs for compliance and ensure that implementation is not vulnerable to a CBP audit. Often, first sale programs are implemented, but are not monitored for continued compliance, and can result in CBP inquiries and penalties. Importers should ensure that they continue to retain supporting documents for a period of five years and review transactions to ensure that they continue to satisfy the arm’s-length pricing tests. Companies may consider, however untested, the Meyer’s court suggestion that the method to establish the absence of non-market influence in antidumping-duty proceedings may also be used in the customs first sale context.

Arent Fox can assist companies that have existing first sale programs to confirm whether existing programs satisfy Customs requirements. If your company has not implemented first sale, we can also explore your duty savings alternatives and design a program that will result in maximum and legally supportable duty savings.

Contacts

- Related Practices